It was during a year abroad in the Netherlands that I first started to carry a sketchbook. It was a transitional period for me. Around the same time, I began thinking about what I wanted to do professionally — and landscape design was coming into focus as one way to marry my horticulture training and love of art and design. In January 2011, I left South Carolina and moved to the rural village of Boskoop near the city of Leiden. I had romantic ideas of working in a nursery, but in reality, it was more of a factory setting — not an ideal situation for this Southerner. I spent those gray January days splitting icy bulbs in a packing shed. I sorted bare-root perennials on a conveyor belt. I got tendonitis from the repetition. I felt as if I was stuck in a Steinbeck novel, and the worst part of all, I missed the South and the ability to share the humor of the situation with friends.

From this experience, I started to learn the language of drawing. (I also tried to learn Dutch, but that didn’t take off). Fortunately, I developed a close friendship with a painter and distant maternal relative, Michiel Schepers, who travels the world painting landscapes and trees. He agreed to give me drawing lessons and I spent every spare moment in his studio. It was during this time that I decided to pursue landscape design. Looking back I now realize the poetic coincidence here since the word landscape is derived from the Dutch, “landschap” — a term coined by early Dutch landscape painters. It was in fact the painterly ways of reading the landscape that I was experiencing in the Netherlands that would inform my future graduate studies in landscape architecture.

Growing up, my father’s influence sparked my interest in art and design from an early age. Although he was a builder and engineer by trade, he was a gifted draughtsman and accomplished painter by hobby. Some of my earliest memories are of him drawing on the front page of our church’s bulletin to pass the time during a lengthy sermon. These were always drawn with tight line-work using a multi-colored Japanese ballpoint pen — a cherished instrument that he always carried. These “church drawings” were wide-ranging in their subject matter, but I mostly remember the drawings that were tied to his memories of places from his childhood in England and, for my boyhood amusement, classic British cars from the 50s and 60s. Because we were in church, I had to patiently wait until after the sermon to get the backstory — how he remembered his grandfather’s vegetable garden, a London street scene with a double-decker bus, or the local pub called the Paul Pry. His drawings were his way of sharing memories of landscape and place in order to share them with the family.

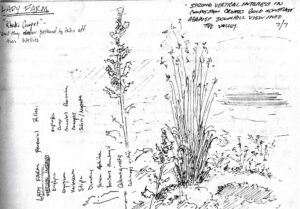

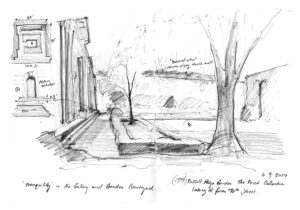

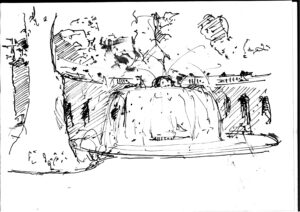

Drawing is both a personal pleasure and working method – my sketchbooks often spark ideas that feed into my work as a landscape architect, whether subconsciously or not. It helps me clear my head and invigorates my spirit. I love to draw because it forces me to slow down and observe closely, allowing me to carefully examine the parts in order to gain a better understanding of the whole. For me, drawing is both meditative and active – it’s a way that I engage with the built environment. I love the tactile act of mark-making and reacting to what the hand/eye has placed on the page. In short, I draw to see better and think more clearly.

My sketches are more than mere souvenirs. I do not try to capture postcard images of the gardens I’ve visited. In fact, some of the grandest gardens I’ve visited have produced my least enjoyable drawings. The gardens and places created for the love of life seem to make the best subjects. For me, one of the great pleasures of visiting any garden is the chance to slow down, sit quietly, and observe carefully. Thus the pages of my notebook are a continuous record of my search for truth and visual notes that attempt to seize on the momentary effects of nature.

As you peruse these drawings, keep in mind that they represent a few “highlights” from about a decade’s worth of travel notebooks. I hope they illustrate how I use drawing as a tool to record my experiences, observe more carefully, or just capture spare moments of life to tell stories. Furthermore, I’ve tried to include a few drawings from gardens that Southern Garden History Society members will undoubtedly recognize.

Leave a Reply