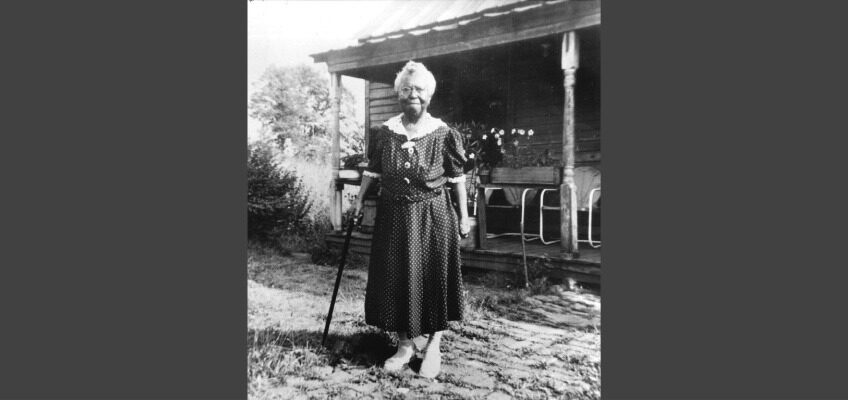

Featured image: Rena Hill, resident of Happy Hill.

Photo Credit: Across the Creek Collection, Old Salem, Inc., Courtesy of Sam McMurray

This article is an update to the an article appearing in the Fall-Winter 1999 issue of Magnolia.

Booker T. Washington delivered the lecture “On Mother Earth” at Tuskegee Institute in 1881. His analogy of a tree’s essential rootedness in the earth to finding one’s bedrock of life was a character-building address for his students. He commended the value of working the land and emphasized the importance of owning the land as foundational. This brings us to the essence of Old Salem’s Hidden Town Project: people and place.

The landscape of slavery is invisible, and the landscape of freedom is compromised; however, identifying and understanding these cultural landscapes are essential, as they are foundational for descendants.

The project research continues to identify People of African descent, build their biographies, and understand their life within the white Moravian world https://www.oldsalem.org/core-initiatives/hidden-town-project/ . Place is more complicated. The landscape of slavery is invisible, and the landscape of freedom is compromised; however, identifying and understanding these cultural landscapes are essential, as they are foundational for descendants.

The Hidden Town Project continues to advocate for revitalization of the historic Happy Hill neighborhood, a historic place brutalized by twentieth-century public policies. This first African American neighborhood in Winston-Salem is called “The Mother of All Black Neighborhoods.” Its origins are in 1872 when the Moravian Church in Salem created a segregated place across Salem Creek for Freedmen who were eager to buy land and build homes for their families. The beautiful rolling landscape of Happy Hill was a stable Black neighborhood until it was repeatedly impacted by decisions made well beyond its control.

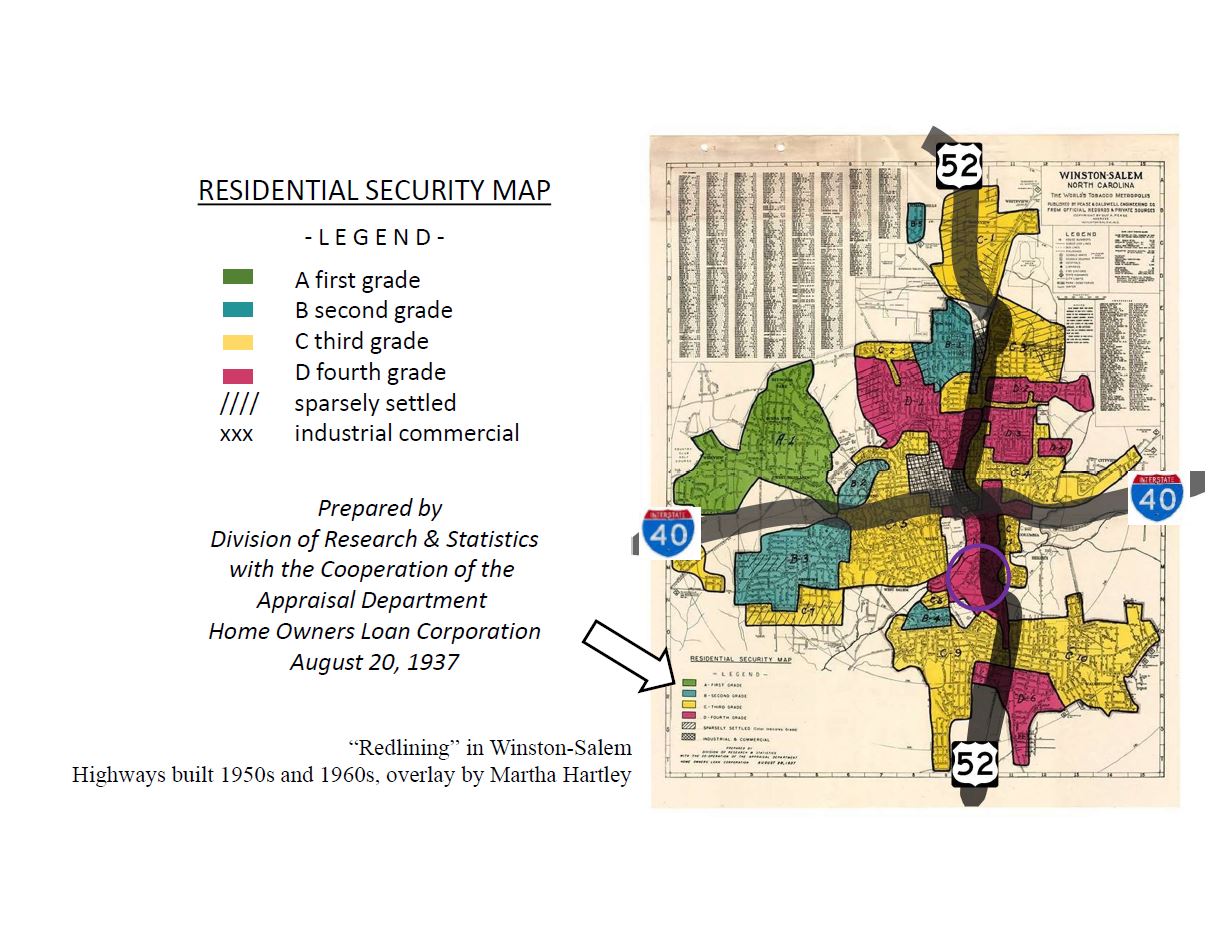

In the United States, residential security maps, or redlining, were formal means of racial discrimination, especially in banking services and insurance, where neighborhoods were graded for quality and desirability. The implications were severe as Black neighborhoods were highlighted as high risks and denied loans or fair loans, and homes were undervalued, all depriving African Americans of wealth-building. Municipal infrastructure was withheld from Black neighborhoods and led to disrepair which often ended with bulldozing. Public policy also targeted Black neighborhoods for urban renewal and highway development. Destruction included homes, businesses, churches, livelihoods, and social fabric as the landscape was ravaged. Displacement…what does that do to one’s foundation? Happy Hill bears the scars on its landscape.

How do we repair the generational damage done to African Americans places? “Reparative Planning” is an emerging concept that seeks to dismantle built-in racist practices, to redress past wrongs, and to create place through inclusivity. Reparation can take many forms but understanding and facing truth in history is basic to the conversation. The pandemic has brought forward an overlooked but major inequity in urban places: access to nature and green space. This derives from the history of displacement, as profiled by Biophilic Cities, an initiative of the University of Virginia’s School of Architecture, that works to build natureful urban places https://www.biophiliccities.org/pandemic-lessons-equitable-urban-nature.

The Hidden Town Project continues to promote public awareness by engaging audiences through conferences, webinars, and special lectures. The project is also in collaboration with the Institute for Dismantling Racism in Winston-Salem on an initiative to provide education in community history and a path forward. A Hidden Town Community Research Fellowship was established to bring descendant participation into the research process, and the 2021 Black History Month Genealogy Regional Conference provided a forum for outreach https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cKlqJmSvx7k&feature=emb_logo . The landscape is cultural memory, visible or not. Our challenge is to reveal the history and to acknowledge the past. Place then becomes the landscape for reparation.

Leave a Reply