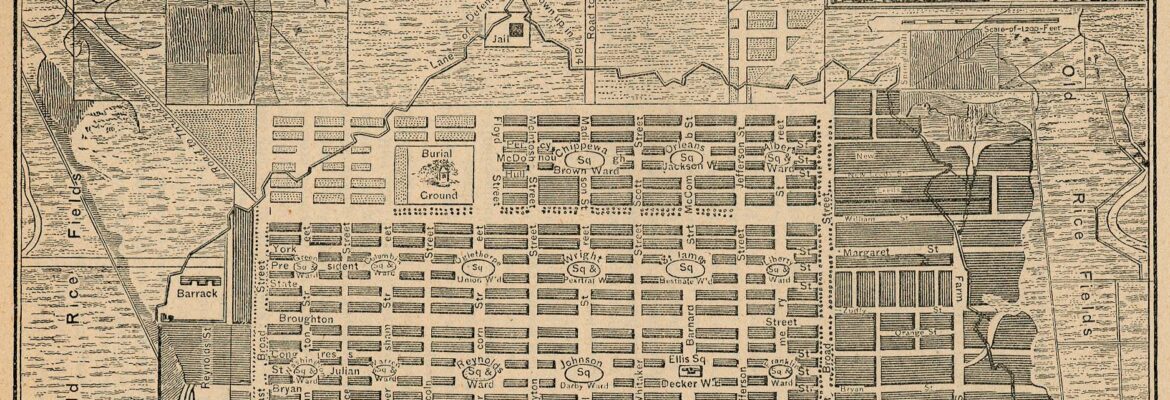

Credit: Wikipedia, Public Domain.

SGHS members have visited Savannah twice for annual meetings, the first occasion coming in 1989 and the second in 2014. Surely each of us came away with strong individual memories. This writer, for example, recalls a visit to the Bonaventure Cemetery grave of native son composer Johnny Mercer and an early morning hotel window view of the majestic Masonic Center, now part of the Savannah College of Art and Design. Collectively, however, we may have been most impressed by the town plan with its famous wards and squares dating back to Savannah’s early eighteenth-century origins.

Our hosts for both meetings offered the background details needed prior to walking and bus visits to neighborhoods deeply rooted in early colonial design. Members thus learned that a colonial footprint had survived here in ways now lost at such early and carefully planned towns as Philadelphia.* The standout person was the Georgia colony’s founder General James Edward Oglethorpe and the crucial date was 1733 when he and over one-hundred settlers began to establish a Savannah River-front town keyed to the notion of egalitarian small-scale farming.** Along with providing leadership for the new colonists, Oglethorpe also played a central role in establishing friendly relations with the region’s indigenous peoples, the Yamacraw, and with their leader, Tomochichi, who gave the land for Savannah’s construction to the General.

Savannah’s famous squares would become its most distinctive features, twenty-two of which are included in the city’s National Historic Landmark district. Oglethorpe again gets credit, as we owe the squares’ existence to the General and to his eponymous town plan. Numerous online and print resources offer detailed discussions and images, but in brief the plan followed a grid pattern of smaller units within a large block, the latter being termed a ward.*** Each ward was centered with a large open area (the “square”) into which ran streets from north, south, east, and west. The four corner areas, in turn, encompassed ten residential lots termed “Tythings,” each bisected by narrow east-west lanes for service access. To the east and west of each square, moreover, the plan allowed for four “Trust Lots,” two on one side and two on the other side of the square and conceived to meet government, commercial, educational, and worship needs. As more colonists arrived additional wards could easily be added to allow for population growth. (Reflecting Oglethorpe’s yeoman farmer ideal, early settlers were also to receive five-acre garden plots and forty-five acre farm allotments on the outskirts of town. See: Land of our Own, 1983 Atlanta Historical Society exhibit catalog, Catherine Howett text, 10.)

Although not long-lived, the ten-acre Trustees’ Garden stands out as another early Savannah feature. Located in the town’s northeast corner and named for the colony’s governing body in England, its chief influence may have been London’s Chelsea Physic Garden. Various sources note that while pleasing to the senses, the Trustees’ Gardens served primarily for experimentation and with an eye toward plants that might be profitably grown in the new thirteenth British North American colony (e.g., mulberry trees for silk production, a long-held dream that was never realized).

Our SGHS Savannah meetings also brought attention to the work of Clermont Lee, a pioneering and prolific native “daughter” landscape architect whose mid-twentieth-century efforts to revitalize segments of her town’s early landscapes led her to be termed the “Saint of Savannah’s Squares.” Society members also became familiar with some of the gardens she designed to complement such important properties as the Green-Meldrim House, the Owens-Thomas House, and the Juliette Gordon Low Birthplace. (Sadly, the latter garden was demolished in 2020, an event chronicled by former board member Ced Dolder in the Summer 2020 issue of Magnolia.) ****

Lastly, in discussing women important to Savannah gardens we should also remember Mary Helen Ray, who in 1989 took the lead in organizing our seventh SGHS yearly gathering. A prominent historic preservation advocate and a regular at Society annual meetings, Mary Helen served as president of the Garden Club of Georgia from 1971-1973 and also became widely known for co-editing The Traveler’s Guide to American Gardens. No one could ask for a warmer or better-informed host.

***********************************************************

*For a video discussion, see*https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ovXWexJBolA

** https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oglethorpe_Plan

***A particularly valuable and highly readable assessment is found in Staci L. Catron and Mary Ann Eaddy (photography by James R. Lockhart), Seeking Eden: A Collection of Georgia’s Historic Gardens, 263-275. See also: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Squares_of_Savannah,_Georgia#/media/File:SchematicSavannahSquare.jpg

****See: https://southerngardenhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Magnolia_Spring2014.pdf#page=1

See also: https://southerngardenhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/Magnolia-NL-Summer-20-FINAL.pdf#page=17

Leave a Reply