Recently our new Southern Garden History Society administrator Aimee Bonnette Moreau shared a photo of zinnias just cut from the garden of Randy Harelson and Richard Gibbs in New Roads, Louisiana. It is a well-composed image, and the zinnias are truly stunning. Those who attended the Natchitoches annual meeting will also recall famed Louisiana artist Clementine Hunter’s depiction of zinnias in some of her most striking works. Of course, for many of us enjoyment of the brightly colored beauty of zinnias is a simple matter of stepping into one’s own garden or taking a walk down the street.

Learning more about these multi-formed and many-hued favorites, as with so many subjects, requires only a mouse click or two. Active–or armchair–gardeners can then spend hours expanding their plant history knowledge and zinnia how-to skills. For those who find long-term staring at computer screens wearisome, there are of course books and articles to be found covering the topic. Highly recommended, for example, is the zinnia section in Popular Annuals of Eastern North America, 1865-1914 by Peggy Cornett Newcomb, (now Peggy Cornett) Magnolia editor and Monticello curator of plants.

These sources inform us that the wild zinnia (Zinnia grandiflora) is a tough native of Mexico and neighboring regions. Though first taken to Europe in the sixteenth century, they get their name (courtesy of Carl Linnaeus) from the German professor of anatomy and botany, Johann Gottfried Zinn (1727-1759). Zinn spent his final years at Göttingen, directing the university’s botanic garden, experimenting with zinnia seeds received from Mexico, and writing about the results.

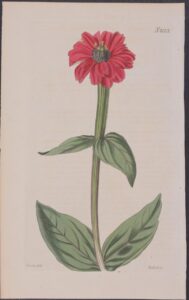

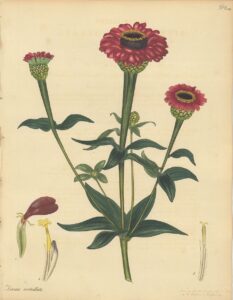

While striking in its natural setting, the Zinnia grandiflora lacked general acceptance by gardeners, particularly in the United States. One 1908 source describes early zinnias as “coarse,” while their colors were called “muddy.” However, a zinnia that came to Europe in the late-eighteenth century, the Linnaeus-named Zinnia elegans, proved to be more popular and commercially successful, especially in France.

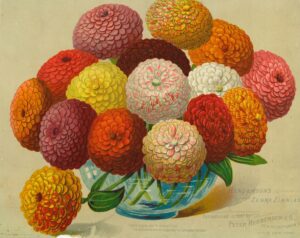

In Popular Annuals the author notes that decades would pass before experiments by French growers resulted in showier zinnias, some bearing a resemblance to the dahlia, a plant also native to Mexico and having a history very similar to the zinnia. Popular Annuals details this period of development during the second half of the nineteenth century, as do a variety of on-line resources.

Work by growers in the U.S. did not forever lag behind developments in Europe. Certain names in particular stand out as grower-entrepreneurs who helped zinnias come into their own in the second half of the nineteenth- and early-twentieth centuries. These include two Philadelphia-based seed suppliers, Thomas Meehan (1826-1901) and Henry Augustus Dreer (1818-1873), along with Californian John Bodger, his “Dahlia Flowered Zinnia” becoming in the 1920s a Bodger seed business standout and continuing success. Interestingly, however, all three individuals had immigrated from either England or Germany.

To explore historic zinnia sources, visit Southern Plant Lists found on our “Resources” page. Confirming observations in Popular Annuals, earlier offerings were highly limited, and one can only guess how much space gardeners were giving to zinnias. In 1802 the famed Philadelphia horticulturist Bernard McMahon listed only “Zinnia multiflora” and Zinnia pauciflora, termed respectively “Red” and “Yellow.” (The common name today of Zinnia pauciflora is Peruvian zinnia.) In 1810, Baltimore “Seedsman” William Booth also offered red and yellow zinnia seeds, common name only provided. Three decades later Arkansan Jacob Smith was growing the above-mentioned Zinnia elegans, exclusively it appears and acquired from an undesignated source. Again, it was a narrow palate indeed.

We know the situation is different now, thanks to nineteenth-century French growers along with work by plant experimenters Meehan, Dreer, Bodger, and many others, today’s gardeners having almost limitless options and sources to spread a wealth of zinnias across the landscape. Their story is summed up in one line on the Chicago Botanic Garden website where zinnias are termed “the hardest-working flower in the summer garden.”

The Zinnia on the Ceiling of Walter Anderson’s Cottage In Ocean Springs, Mississippi

By Randy Harelson

The locally famous Gulf Coast artist Walter Anderson is considered by this writer one of the finest American artists of the twentieth century. Born in New Orleans in 1903, Anderson lived most of his life in or near Ocean Springs, Mississippi. His extraordinary work as an artist included painting in oil and watercolor, pen-and-ink drawing, linoleum-cut block printing, building and decorating pottery (with his family’s famous Shearwater Pottery), woodcarving, and mural development and painting for Ocean Springs’s high school, community center, and a small room in the artist’s own home on the grounds of Shearwater Pottery.

The small mural completed in the last years of Anderson’s life – he died in 1965 – is a depiction of a single day in the life and spirit of the Mississippi Gulf Coast, and also an illumination of Psalm 104.”The Lord wraps himself in light as with a garment.” Psalm 104:2

The mural covers the four walls and ceiling of a room only 12-by-14 feet. The artist kept the room locked until his death. When his wife and children entered the room after his death they were amazed by what they saw. The plants and animals of the Gulf Coast come to life on the four walls, magically progressing from dawn to dusk and on through the night. The ceiling is covered almost entirely with an image of a single zinnia flower, suggesting the glowing sun in the noonday sky.

In a short poem, Anderson writes:

Oh, zinnias,

Most explosive and illuminating

Of flowers,

Summation of all flowers,

Essence of excentric form,

Essence of concentric form!

Clearly Anderson considered the zinnia of enormous importance both in its placement in his mural, and in his writing of it so emphatically.

https://www.walterandersonmuseum.org/littleroom

Randy Harelson’s Notes:

- In his poem, Anderson spells “Excentric” in his own eccentric way.

- A beautiful essay by Redding Sugg makes up the text of the book A Painter’s Psalm: The Mural in Walter Anderson’s Cottage with photographs by Gil Michael (Memphis State University Press, 1978)

- Redding Sugg is also the editor of The Horn Island Logs of Walter Inglis Anderson (Originally published Memphis State University Press, 1973. Currently in print, University Press of Mississippi, 2020)

- The Walter Anderson Museum of Art in Ocean Springs has a good website with photographs of the little room and its extraordinary mural.

Leave a Reply