By Wayne Amos and Gail Griffin

Another beautiful species of Lycoris to surprise Southern gardeners in late summer is L. squamigera, known as the magic lily or naked lady. Hardy farther north than L. radiata, which was described on this website in July, L. squamigera flourishes from Maine to Texas, but needs some winter chilling to bloom well.

In A Southern Garden, Elizabeth Lawrence describes L. squamigera, which she calls Hall’s amaryllis, as “four to seven fragrant, opalescent flowers borne in umbels on tapering, thirty-inch scapes. The petals are like a changeable silk in Persian lilac with tints of violet.” Her friend William Lanier Hunt of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, one of the three founders of the Southern Garden History Society, suggests in Southern Gardens, Southern Gardening that L. squamigera, which he calls the pink spider lily, is a good companion to camellias (along with Lycoris radiata and Sternbergia lutea) in shady woodlands.

According to botanist Sereno Watson in Garden and Forest, April 9, 1890, L. squamigera was introduced to America from China in 1862 by Dr. George R. Hall, of Bristol, Rhode Island, and distributed subsequently as Amaryllis hallii by seedsman Charles Mason Hovey of Boston. It was first described in 1884 in Botanische Jahrbücher by Estonian botanist Carl Johann Maximowicz, who collected the plant on the Japanese island of Kyushu. The genus Lycoris honors the Roman mistress of Mark Antony and the species squamigera refers to the iridescent scales on the petals.

Although usually listed as a species, L. squamigera is a sterile, triploid hybrid, which adds to its vigor. Its parentage is uncertain; perhaps it is an intentional or a natural hybrid of L. longituba x L. sprengeri or L. sprengeri x L. chinensis.

Photograph courtesy of J. C. Raulston Arboretum

Photograph courtesy of J. C. Raulston Arboretum

Lycoris is a member of the Amaryllidaceae family (other genera include Agapanthus, Amaryllis, Hippeastrum, Crinum, Galanthus, Leucojum, and Narcissus) all of which contain a mixture of toxic alkaloids, including galantamine and lycorine, which not only protects the plant from being eaten, but was given to Odysseus by Hermes to protect from Circe’s poison and is used today in the treatment of dementia and other diseases.

The large, brightly colored eastern lubber grasshopper, Romalea microptera, found in the Southeast from North Carolina to Texas, feeds on over one hundred plant species including members of the Amaryllis family. This past summer in the Athens garden of SGHS members Wayne Amos and Charlie Hunnicutt, lubbers munched happily on Lycoris and Crinum, ingesting alkaloids that would be poisonous to predators that would eat them, but predator Wayne, undeterred by their warning coloration, zapped them instead.

Cultural information from predator horticulturist Wayne Amos:

Lycoris squamigera is among the hardiest and most vigorous of the genus and has been cultivated in the US for well over a century. The foliage is produced in the fall to spring, and the bulbs are leafless when the flower stalks emerge in late summer. They seem to prefer light shade and even moisture but will tolerate and even flourish in full sun. The flowers last longer with a bit of afternoon shade when in bloom. They are cultivated in USDA zones 5 through 9, prefer deep rich soil, but tolerate a range of less perfect soils as well.

Planting depths are recommended in the 5 to 8 inches range with 2 to 4 inches of soil over the top of the bulb. Moderate fertilization in the fall as a top dressing is sufficient. Care should be observed in planting to allow for the abundant spring foliage, which must ripen completely before removal to ensure continued flowering. Bulbs are best dug and divided when summer dormant, about six weeks after foliage goes dormant. Lycoris resents drying and removal of roots, so it is best to keep them damp and replant as soon as possible. They often sulk for a couple of years when transplanted and do not bloom, so mark their place in the garden to prevent accidental damage or planting over while out of sight. Lubber grasshoppers have attacked flower buds and stalks in my Athens garden, the only insect pest observed.

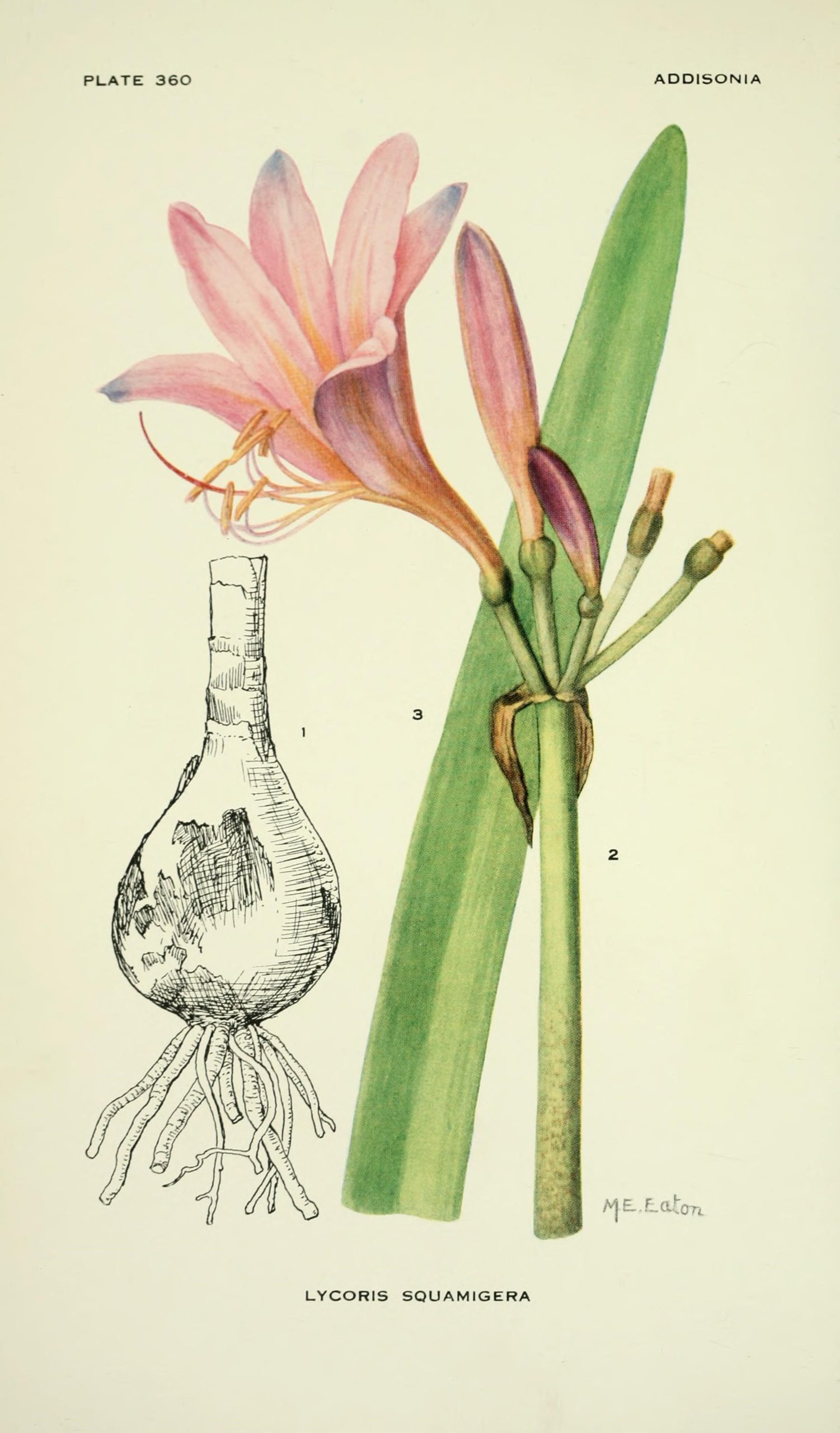

In the years since L. squamigera was found in eastern Asia, its beauty has attracted artists. In 1897, Matilda Smith, key illustrator for over forty years for Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, made a detailed drawing of L. squamigera that illustrates the blue tips of the petals, the yellow throat within the flower, the tennis ball sized bulb, and the lush, greyish-green, round-tipped foliage.

When I was at Dumbarton Oaks, every year in early August, Wayne called to ask if there were naked ladies in the garden. As you can see in this photograph taken there last week by staff member Marc Andreas Vedder, the naked ladies are still covering the hillsides in lusty profusion.

Ione Coker Lee

Gail,

I enjoyed reading about L. squamigera or Naked lady. My favorite has been L. radiata, the red spider lily which

blooms during my birthday month, September. But I’m happy to learn about the pink lady you and Elizabeth Lawrence describe so beautifully. I dabble at botanical drawing and loved the historic botanical drawings you included.

I miss the annual meetings and look forward to seeing you there when next we convene.

Ione